La tragedia nel tempo della festa

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.13135/2038-6788/9671Parole chiave:

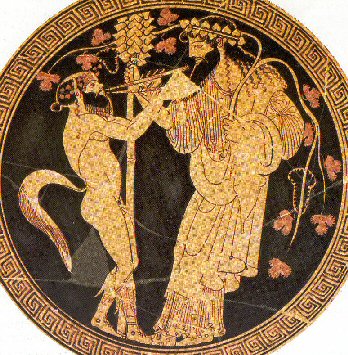

Capro, Dioniso, Eraclito, Festa, Tragedia, Unità della vitaAbstract

Nietzsche’s Birth of Tragedy was strongly criticized by Wilamowitz with the argument that tragedy has no essential relation with the Dionysian religion, least of all if it is interpreted, as Nietzsche does, as an anticipation of Schopenhauer’s philosophy. This paper will demonstrate the reliability of such criticism through an historical analysis of the development, the content, and the mythological background of the four Dionysian festivals that constituted the traditional framework for all dramatic performances in classical Athens: the Rural Dionysia, the Lenaia, the Anthesteria and the City Dionysia. The result is that, except for the last (and chronologically later) one, in their foundational myth all three earlier festivals had a somehow dark side, an allusion to suffering, death, and the netherworld even when people attended them in an apparently joyful and rowdy atmosphere. It is especially Dionysus’ double nature, his ambiguity between life and death, his coping with an enemy whom he finally turns into a wretched double of himself, that spur the evolution of the tragic ritual into a conflict of characters and a tragic spectacle. The origin of Greek tragedy can thus hardly be explained on the basis of a simple ceremony in honor of the gods or some other national hero. It is not incorrect to speak of a “Dionysian vision,” i.e., Dionysus’“dialectic,” as the inspirational ground for Greek tragic theatre, although themes pertaining to the god and his stories are actually rarely present in the now extant tragedies.